Don’t Talk about Implicit Bias Without Talking about Structural Racism

by Kathleen Osta, LCSW and Hugh Vasquez, National Equity Project

Implicit bias has been in the news a lot lately. At the National Equity Project, we think it is an important topic that warrants our attention, but it is critical that any learning about implicit bias includes both clear information about the neuroscience of bias and the context of structural racism that gave rise to and perpetuates inequities and harmful racial biases. As leaders for equity, we have to examine, unpack and mitigate our own biases and dismantle the policies and structures that hold inequity in place. We call this leading from the inside-out.

Most work on implicit bias focuses on increasing awareness of individuals in service of changing how they view and treat others. This is important, but insufficient to advancing greater equity of opportunity, experience, and outcomes in our institutions and communities. Rather, in order to lead to meaningful change, any exploration of implicit bias must be situated as part of a much larger conversation about how current inequities in our institutions came to be, how they are held in place, and what our role as leaders is in perpetuating inequities despite our good intentions. Our success in creating organizations, schools, and communities in which everyone has access to the opportunities they need to thrive depends on our willingness to confront the history and impacts of structural racism, learn how bias (implicit and explicit) operates, and take action to interrupt inequitable practices at the interpersonal, institutional and structural level.

We believe the work we need to do begins on the inside — inside of ourselves, inside of our own organizations, and in our own communities. We offer the metaphor of a window and a mirror (developed by Emily Style of the SEED Project) for increasing our equity consciousness and understanding what is needed to take effective leadership for equity. Each of us needs to look in the mirror to notice how our particular lived experiences have shaped our beliefs, attitudes, and biases about ourselves and others. And, with increased knowledge of ourselves, we also need to look out the window to understand how racism, classism, sexism and other forms of systemic oppression operate in our institutions to create systemic advantage for some groups (white, male, heterosexual, cisgender, etc.) and disadvantage for other groups (people of color, women, LGTBQ+ people, etc.) in every sector of community life.

“As a white woman, my own work on implicit bias starts with myself and a look into when and how, despite my twenty five years of working in the “equity” field, my own thoughts and decision making can be impacted by implicit bias. For example, when out for a run recently, I saw a woman who appeared to be Latina walking out of her home. The immediate thought that popped into my head was “housekeeper.” I had to stop and consider, how did that happen? Regardless of my stated and lived commitment to fairness and justice, my close relationships with Latinx friends and colleagues, and my knowledge of implicit bias, my brain made a potentially harmful snap judgment about who someone was.”

“I am a mixed heritage Latino. Years ago I was co-directing a youth program that focused on what we called “unlearning racism.” We worked with teenagers to develop their consciousness about oppression, build alliances across race, gender and other social identities, and create young leaders who would work to eliminate racism. As adults running this program, we went through intensive training to become conscious of our own racial identities and work to eliminate our biases so that we could help youth eliminate theirs. One hot summer afternoon I was driving to lunch, windows down. I stopped at a red light and I immediately noticed 3 young African American boys crossing the street in the crosswalk in front of my car. They were 6th graders, 11 or 12 years old. As they crossed, one of them looked at me and yelled “go ahead, roll up your windows!” I was livid with him for assuming I would be afraid and roll up my windows out of fear. But as they walked past me and finished crossing the street, I calmed down, stopped staring at them, and was shocked to see that my hand had moved from the steering wheel to the window switch and I was ready to roll up the window. I had moved my hand to roll up the window without conscious awareness that I had done so. Even after all my training and consciousness raising to eliminate racism, my unconscious mind reacted with fear to these young African American boys. How could this happen?”

To understand how this happens, it is important to understand that our brain is like an iceberg with the conscious part of our brain being the smaller part of the iceberg that we can see above the water line, while the larger part of the iceberg, where our unconscious processing takes place, is below the water line. Research shows that the unconscious mind absorbs millions of bits of sensory information through the nervous system per second. Our conscious minds are processing only a small fraction of this information and doing so much more slowly and less efficiently than our unconscious minds. This means that we have a lot going on in our brains that we are not consciously aware of. Have you ever driven all the way home from work, but not had any memory of doing so? Your brain was processing all of the information needed and guiding your decision making for your safe arrival home even when your conscious mind was not active. In order to process all of the information needed to survive, our brain creates shortcuts to quickly assess our environment and respond in ways that keep us safe from danger. For example, if you were walking down a path or on a street and heard a strange noise or a rustling in the bushes, your amygdala would immediately send a danger alert which would activate your fight, flight, or freeze response. This would all happen before you had consciously processed the danger. If we were to count on the much slower processing of our conscious brain in these instances of perceived danger, the human race wouldn’t have survived very long.

How does all of this connect to implicit bias and structural racism? Let’s start with a definition of implicit bias:

Implicit Bias is the process of associating stereotypes or attitudes towards categories of people without conscious awareness.

Note that this is not the same as explicit, conscious racism and other forms of conscious bias which still exist and need to be addressed. Here, we are talking about people who consciously and genuinely believe in fairness, equity, and equality, but despite these stated beliefs, hold unconscious biases that can lead us to react in ways that are at odds with our values. These unconscious biases can play out in our decision making regarding who we hire for a job or select for a promotion, which students we place in honors classes and who we send out of the classroom for behavior infractions, and which treatment options we make available to patients. We know from extensive research that this kind of biased decision making plays out all the time in our schools, in hospitals, in policing, and in places of employment. The question is not if it is happening, it is when is it happening and what can we do about it.

Implicit bias and its effects play out through three keys processes: Priming, Associations, and Assumptions. Priming is a psychological phenomena in which a word, image, sound, or any other stimulus is used to elicit an associated response. Some of the best examples of priming are in product advertising in which advertisers prime us to feel an affinity or emotional connection to a particular brand that leads us to choose that brand over others even when there is actually no difference between the products. We buy Nikes because we are compelled to “Just do it.” We think we are consciously choosing, but our unconscious mind is doing the shopping. But product selection is not the only thing influenced by priming — so are our beliefs, views and feelings about others.

The Associations we hold about groups of people are created and reinforced through priming. Associations occur without conscious guidance or intention. For example, the word NURSE is recognized more quickly following the word DOCTOR than following the word BREAD. We associate two words together because our unconscious mind has been wired to do so. Quick — what do cows drink? Not milk! But we have a strong association in our brain between cows and milk. (Cows drink water.)

When it comes to people, the associations our brain makes works the same way, creating shortcuts based on how we have been primed. The way our brains create shortcuts to quickly make sense of data is innate. How we have been primed to make harmful associations about different categories of people is not, but is rather the result of messaging, policies and practices that have been applied throughout history to include or exclude groups of people.

The United States has a long history of systemic racism — since the founding of the country stories that dehumanized African Americans and Native peoples were used to justify genocide, slavery, racial segregation, mass incarceration, and police brutality. Negative and dehumanizing stereotypes about women and people of color and stories that “other” are rampant in the news media and in popular culture. For example, we have been primed throughout history by our own government, by popular culture, and through the media to think of African American people as less intelligent, aggressive, and more likely to commit crime. We have received unrelenting messages that people who are immigrating to the United States from Central America and Mexico are criminals. Likewise, we have been primed to think of women as less competent, overly emotional, and their bodies as objects to be judged. For every stigmatized group of people, we have been repeatedly exposed to stereotypes that most of us can readily name that have been used to justify policies that have further stigmatized and marginalized.

“Implicit biases come from the culture. I think of them as the thumbprint of the culture on our minds. Human beings have the ability to learn to associate two things together very quickly — that is innate. What we teach ourselves, what we choose to associate is up to us.”

Think back to the autopilot moments we shared in our own stories. Consciously, we knew that the woman coming out of the house was most likely the homeowner, on her way to work, and that the boys crossing the street were simply on their way back to school, but our unconscious brain created shortcuts based on repeated priming about who Latina women and Black boys are — thus producing harmful associations and reactions in both of us. This priming is then reinforced by the current structural arrangements in our communities in which people of color and people living in poverty have been disproportionately cut-off from high quality educational experiences and high-paying jobs. Consider who we most often see cleaning our hotel rooms, busing our tables, and landscaping yards and who we most often see being sent out of classrooms, pulled over by police and jailed. The more we see (or hear) two things together, the stronger the association — this is the way neural pathways are built. Brain cells that fire together, wire together. What associations are being created in our brains based on how we are primed through everyday experiences in our own communities, through news coverage, advertising and other forms of media?

Our brain is scanning our environment for who belongs (and is safe) and who is “other” (and a potential threat or dangerous). Who we come to categorize as belonging or threatening is learned as a result of structural inequities and messaging we have received about categories of people. These harmful associations we carry can lead us to make Assumptions that have life and death consequences for people of color. We saw this when:

The police were called by a Starbucks manager because she made the association that Rashon Nelson and Donte Robinson, two African American men, were dangerous, resulting in their arrest when they were simply waiting to meet someone.

Two Native American young men, Kanewakeron Thomas Gray and Shanahwati Lloyd Gray, drove from New Mexico to go on a college tour at Colorado State University and a white mother who was also on the tour called campus security because they looked like “they don’t belong, they were quiet and creepy and really stand out.” Security came and questioned the young men and confirmed that they were registered for the campus visit, but by the time they were released, the tour had gone ahead without them and they ended up driving home without a tour at all.

Tamir Rice, a 12 year old African American boy was in a park with a toy gun when police drove up and within two seconds of exiting the vehicle an officer shot and killed him.

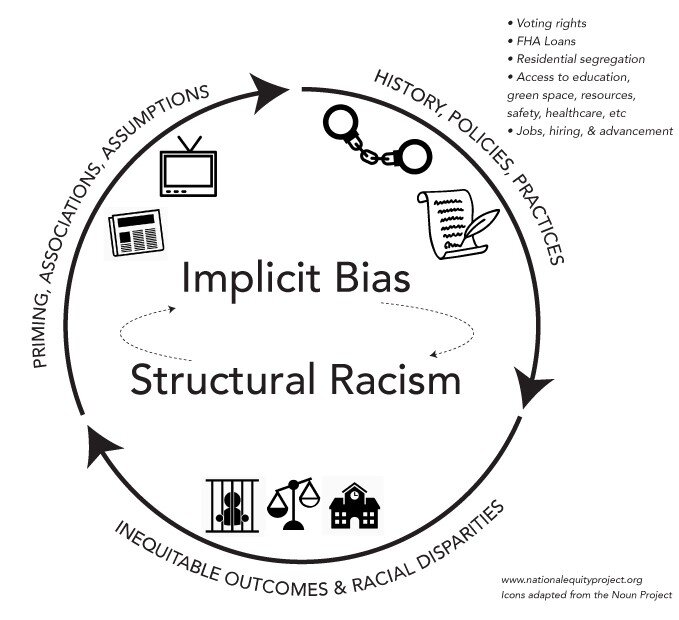

These incidents and many more like them sit in a larger context of racial segregation, exclusion, and systemic inequities in which society’s benefits and burdens are distributed unevenly depending one’s race. Professor john powell of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society calls this “structural racialization” — referring to institutional practices and structural arrangements that lead to racialized inequities — as we see in the case of education, health, housing, criminal justice, and even life expectancy in the United States. These two phenomena — structural racialization and implicit bias — work dynamically to hold inequities in place. This is why we believe learning about implicit bias is an important, but an insufficient strategy to advance equity.

“Those who practice leadership for equity must confront, disappoint, and dismantle and at the same time energize, inspire, and empower.”

Making progress on equity will require us to both mitigate our own biases and change structures. For example, structural inequities in the way we fund our public schools mean that students living in affluent communities (most often majority white) attend highly resourced schools with extensive opportunities for deep learning and extra-curricular activities while students living in neighborhoods in which we have disinvested (often majority people of color) attend schools that are underfunded with fewer academic and extra-curricular opportunities. When these students underperform, the fact of their underperformance reinforces our conscious and implicit stereotypes about their intelligence, the extent to which their parents value education (they do), and their effort. This is an insidious cycle whereby the structural inequities produce inequitable outcomes which then reinforce harmful stereotypes about students of color and students living in poverty and which are then used to justify inequitable practices such as holding low expectations, academic tracking, and punitive discipline in schools.

“Biases not only affect our perceptions, but our policies and institutional arrangements. Therefore, these biases influence the types of outcomes we see across a variety of contexts: school, labor, housing, health, criminal justice system, and so forth….These racialized outcomes subsequently reinforce the very stereotypes and prejudice that initially influenced the stratified outcomes.”

As leaders for equity it is our responsibility to look at how our own biases and biases within our organizations contribute to structural inequities and advocate for policies that increase access to economic, educational, and political opportunity. We must expand our notion of success to include diverse perspectives and values. In education, this means providing culturally sustaining opportunities for rigorous intellectual work and healthy social emotional and physical development for all of our young people, not just those born in affluent zip codes. Many schools and school districts are actively engaged in efforts to change structures to mitigate the effects of bias and increase educational equity within schools and across communities. Some examples of these changes include:

Expanding professional learning opportunities for educators to learn about how systemic oppression operates to increase their awareness of their own cultural frames and gain strategies for building learning partnerships with students whose lived experience is different from their own.

Eliminating subjectivity in placement decisions for AP/Honors courses by requiring students to “opt out” rather than relying solely on teacher recommendation, thus increasing the numbers of students of color and students living in poverty in high-level courses.

Implementing policies in which the most experienced and talented teachers are teaching the students with the highest level of academic need, and not the other way around (as is often the case).

Enacting laws that make it harder for childcare centers to expel preschoolers and creating diversion programs in which School Resource Officers refer students to social service agencies for support, instead of arresting them.

Changing discipline policies whereby only the most serious negative behaviors are subject to suspension and implementing a system of checks and balances in which a trusted adult is called to the classroom when a behavior challenge arises rather than sending students out of class in order to mitigate racial bias.

Examples of structural changes across schools might include:

Enacting legislation providing for competitive federal grants to districts to support voluntary local efforts to reduce school segregation.

Bolstering Fair Housing legislation to reduce discriminatory zoning policies that effectively exclude low-income and families of color from high performing and well resourced schools by banning apartment buildings and other multifamily units in nearby neighborhoods.

Mandating a federal review of efforts by wealthy and predominantly white school jurisdictions to secede from integrated school districts.

Strong efforts to acknowledge, interrupt, and mitigate the effects of implicit bias will require us to engage in on-going mirror work, exploring our own biases and paying attention to how we are primed to think about categories of people while simultaneously engaging in window work, looking at our current context with a systemic and historic lens so that we can dismantle inequitable policies and structures and create new structures in which we all experience belonging and can thrive.